Francisco J. Valero-Cuevas, Ph.D.

AIMBE College of Fellows Class of 2014 For outstanding contributions to the mathematical and engineering understanding of the neural control of limbs to produce versatile function.

Motor Control Development May Extend into Late Adolescence, Study Finds

Via University of Southern California News | September 18, 2013The development of fine motor control — the ability to use your fingertips to manipulate objects — takes longer than previously believed and isn’t entirely the result of brain development, according to a pair of complementary studies by USC researchers.

The studies open up the potential to use therapy to continue improving the motor control skills of children suffering from neurodevelopmental disorders such as cerebral palsy, a blanket term for central motor disorders that affects about 764,000 children and adults nationwide

“These findings show that it’s not only possible but critical to continue or begin physical therapy in adolescence,” said Francisco Valero-Cuevas, corresponding author of the studies that will appear in the Journal of Neurophysiology and The Journal of Neuroscience, two leading publications in the field.

“We find we likely do not have a narrow window of opportunity in early childhood to improve manipulation skills, as previously believed, but rather developmental plasticity lasts much longer and provides opportunity throughout adolescence,” he said. “This complements similarly exciting findings showing brain plasticity in adulthood and old age.”

USC Engineer Breaks Down Barriers, Spurring Research

Via University of Southern California News | August 23, 2013Step into Francisco Valero-Cuevas’ Brain-Body Dynamics Lab at USC, and you’ll find a neuroscientist, biomedical engineer and mechatronics engineer among the eight researchers who come from different backgrounds and varied research interests.

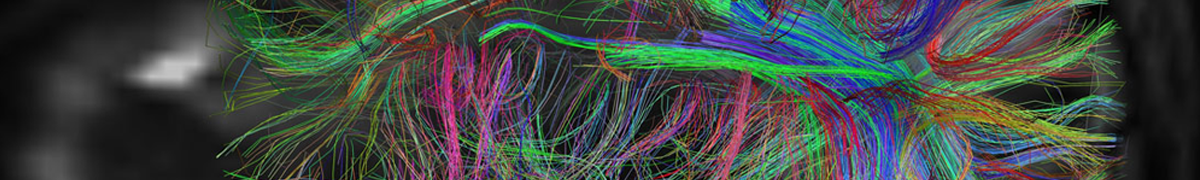

Valero-Cuevas, professor of biomedical engineering, biokinesiology and physical therapy at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, studies how the brain controls our bodies. He also has a knack for bringing students together to work toward a common goal. And these days that means finding possible solutions for the increasingly complex challenges facing medicine, science and robotics.

This summer Valero-Cuevas worked with students from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), the country’s largest public university, during a summer internship.

The handpicked students spent eight weeks in a lab that aligned with their personal interests. If they liked the program, they could apply for a USC PhD program whose costs would be covered by a fellowship.

The program was designed as part of an agreement that Valero-Cuevas and USC Viterbi Dean Yannis C. Yortsos created between USC and The National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACyT) in 2010.

AIMBE

AIMBE