Frederick R. Haselton, Ph.D.

AIMBE College of Fellows Class of 2007 For outstanding contributions to research and teaching in cell bioengineering, endothelial function, retinal pathophysilogy and, microarray technology.

Team receives $4 million NIH grant for rapid test of COVID-19, other respiratory infections

Via Vanderbilt University | October 13, 2020 Twice in 2019, Nick Adams and his colleagues applied for federal grant money to develop a rapid, precise, in-office test for respiratory infections. This test would skip the time-consuming and expensive steps of purifying the samples for testing or sending them to a lab. Doctors and their patients would not have to wait days, sometimes weeks for results.

Twice in 2019, Nick Adams and his colleagues applied for federal grant money to develop a rapid, precise, in-office test for respiratory infections. This test would skip the time-consuming and expensive steps of purifying the samples for testing or sending them to a lab. Doctors and their patients would not have to wait days, sometimes weeks for results.

Their proposal got high marks for innovation. But the reviewing panel at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, questioned its significance. Among the comments: Existing tests worked fine for diagnosing seasonal flu and pneumonia. What’s wrong with sending samples to a lab?

What a difference a year makes.

In June 2020 the reviewers were more receptive, and in September the NIAID awarded the team a five-year grant of nearly $4 million to develop a panel of quick tests to diagnose COVID-19 infections, seasonal flu and other respiratory illnesses. Adams, research assistant professor of Biomedical Engineering, had updated the application with information about the COVID-19 pandemic, shortages of testing components and an anticipated surge in demand for more widespread, frequent testing.

“Despite the initial funding rejections, we are fortunate to have continued to work toward developing a better test for respiratory illnesses,” Adams said. “We knew we had a good idea, but I guess we just had to wait for others to recognize it… Continue reading.

New field test for malaria drug resistance on horizon

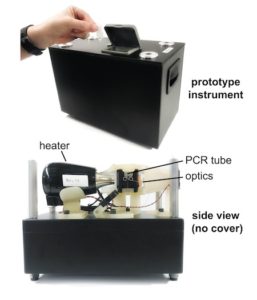

Via Lab Pulse | June 13, 2019By altering the technical design of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for malaria drug resistance, it’s possible to build a simpler, faster assay suitable for testing whole blood in the field, particularly in low-resource settings, Vanderbilt University researchers reported June 13 in a proof-of-principle study published online in the Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

……

The study establishes the principle of a new approach, but it may take years for the test to be validated and broadly available. The most likely use for the technology would be in low-resource settings, said Frederick Haselton, PhD, who has patented the PCR instrument but not the underlying molecular biology tools, along with Nicholas Adams, PhD, both co-authors. These types of assays are usually vetted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and then rolled out on a country-by-country basis, Haselton explained in an email to LabPulse.com… Continue reading.

DNA Duplicator Small Enough To Hold In Your Hand

Via Vanderbilt | January 12, 2017Imagine a “DNA photocopier” small enough to hold in your hand that could identify the bacteria or virus causing an infection even before the symptoms appear.

This possibility is raised by a fundamentally new method for controlling a powerful but finicky process called the polymerase chain reaction. PCR was developed in 1983 by Kary Mullis, who received the Nobel Prize for his invention. It is generally considered one of the most important advances in the field of molecular biology because it can make billions of identical copies of small segments of DNA so they can be used in molecular and genetic analyses.

Vanderbilt University biomedical engineers Nicholas Adams and Frederick Haselton came up with an out-of-the-box idea, which they call adaptive PCR. It uses left-handed DNA (L-DNA) to monitor and control the molecular reactions that take place in the PCR process.

AIMBE

AIMBE