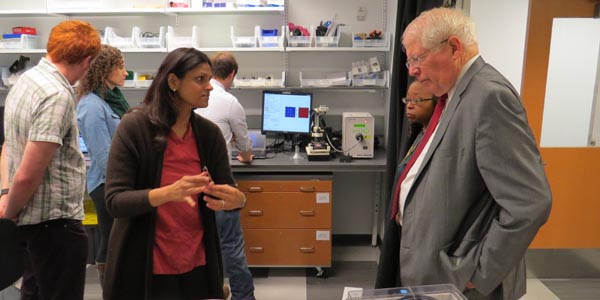

The visit was inspired by Nimmi Ramanujam’s congressional briefing on Capitol Hill hosted by AIMBE to inform legislators about the impact of her federally funded research aimed at improving cancer screening and treatment on a global scale. Price is on the Committee on Appropriations and has long had an interest in health care, both at home and abroad, which led to his visit to see Ramanujam’s work first-hand.

During his visit, Price learned about Ramanujam’s various research projects, which focus on improving health outcomes through improved patient experience and reduced cost, both in the United States and in developing nations.

Graduate student Brandon Nichols talked about his work in breast cancer imaging. During an operation to remove a tumor, surgeons face the difficult challenge of removing all of the cancerous tissue while leaving behind as much healthy tissue as possible. A significant number of patients, however, return for a re-excision surgery that could be avoided if the margins were evaluated in the operating room during the initial surgery.

Ramanujam’s group was funded under an NIH Bionegineering Research Partnership grant to develop a portable imaging system to mitigate the need for extra surgeries. The device uses differences in how various wavelengths of light interact with breast tissue to spot residual cancerous areas. The technology has been tested on more than 100 patients to date and is the size of a laptop.

The second research focus is seeking to find a better way to screen cervical cancer, especially in low-income countries and regions of the United States where cervical cancer is most prevalent. Current best practices involve separating the vaginal walls with a speculum and using a bulky, expensive device called a colposcope from the outside of the body to visually inspect the cervix for troublesome areas in women with positive Pap smears.

This process is uncomfortable at best for women, and impractical to use in a community setting. Ramanujam’s solution is to consolidate the colposcope into a device the size and shape of a tampon and make it speculum free. Such a device would bring secondary prevention into a primary care setting, eliminating the need for referrals.

“The mortality rate of cervical cancer should absolutely be zero percent because we have all the tools to see and treat it,” said Ramanujam. “But it isn’t. That is in part because either women are not screened or women who are screened do not seek a confirmatory diagnosis via colposcopy.”

Ramanujam’s team is working on what amounts to a pocket-sized tampon with lights and a camera. Not only could this allow women to get images of their cervix themselves, it would open up the possibility of trained professionals a continent away doing the diagnoses—or even a computer doing it autonomously.

Diagnosis is only the first step of a solution, however, as treatment options are few and far between as well for remote locations. For that challenge, Ramanujam is working on a method to deliver gelatinized ethanol to kill problematic cells, though that work is still in its infancy.

Price, for his part, was very interested in the research and asked poignant questions throughout his visit. Afterward he remarked, “I’ve been meaning to visit and learn about these projects for a long time. These technologies need to be accessible to the layman for them to be effective, and they certainly seem to be as I was able to follow along easily. You all are doing a great job.”

AIMBE

AIMBE